The article, “The Felt Need” by Dan and Chip Heath in the November, 2010 issue of Fast Company is worth the price of the annual subscription for it’s reminder value alone.

The article, “The Felt Need” by Dan and Chip Heath in the November, 2010 issue of Fast Company is worth the price of the annual subscription for it’s reminder value alone.

The Heaths tackle a topic that just about all of us involved in selling, marketing or strategy have succumbed to at some point in our careers: the felt need versus the burning need.

“If entrepreneurs want to succeed…they’d better be selling aspirin rather than vitamins. Vitamins are nice; they’re healthy. But aspirin cures your pain; it’s not a nice-to-have, it’s a must have.”

The article speaks to our tendency to become enamored with our own ideas and offerings, and to make the leap that because everyone can benefit from this (a vitamin), they will jump at the opportunity to buy. They provide a number of great examples from the publishing and technology arenas.

In my own experience, technology businesses do this all of the time, often as they race to either out-feature competitors or to blindly reflect the input of customers. Not that beating competitors or listening to customers are bad ideas, but both can lead you down blind trails if you’re not careful.

I know better than to fall victim to “The Felt Need,” yet, I’ve produced a number of vitamins during the past few years. On several occasions, I’ve invested considerable time in creating programs that I would take a bullet for as offering career-critical content. While no one disagreed with me on the importance of the programs or the value of the content, they responded to them much like people respond to their gym membership in February.

4 Ideas to Avoid Falling Victim to The Felt Need:

1. Measure and monitor the success of your new offerings. Are they selling like vitamins or, are they selling like aspirins. If you’re listening to your clients properly, they will tell you loud and clear what level of pain that you are addressing.

2. Evaluate new offerings and investment ideas with the filter of “The Felt Need.” It’s not difficult to assess if your marketer, developer or product manager can substantiate true audience pain. Ask tough questions. I love people that are passionate about their ideas, however, I still advocate a “trust but verify before investing” approach.

3. Quality-check your “Voice of the Customer” processes. Many a well-intentioned firm or product manager has listened carefully to customers only to find out that the requests, while valid, were not material. Too much blind followership leads to a bad case of The Innovator’s Dilemma.

4. Cultivate the practice of social anthropology. Ensure that your people are out in the market and in customers’ businesses observing. Ask someone a question and you will get an answer, but watch them in their own environment and you will learn something about them.

The Bottom-Line for Now:

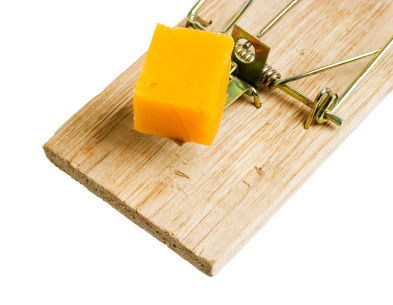

Read the article and spend some time looking at your own mix of current and planned offerings. While as the article indicates, you might end up with some vitamins, you better have a good number of aspirins to address burning pain points. Make certain that your primary strategy is not “follow the competitor” or, “the customer’s need is our command.” You need good systems and great people to observe, translate and mostly uncover true pain points that merit a cure. And remember the Heath’s warning about building a better mousetrap. Most people aren’t interested in a better mousetrap. They simply want a dead mouse.